| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

A Byronic Vampire is a variation of the Byronic Hero, and thus the article about Byronic Heroes from Wikipedia is used:

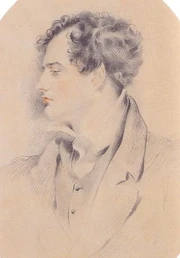

Lord Byron, author and poet

The Byronic hero is a variant of the Romantic hero as a type of character, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron. Although there are traits and characteristics that exemplify the type, both Byron's own persona as well as characters from his writings are considered to provide defining features.

Origins[]

The Byronic Hero first appears in Byron's semi-autobiographical epic narrative poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–1818). Historian and critic Lord Macaulay described the character as "a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his brow, and misery in his heart, a scorner of his kind, implacable in revenge, yet capable of deep and strong affection".[1] The initial version of the type in Byron's work, Childe Harold, draws on a variety of earlier literary characters including Hamlet, Goethe's Werther (1774), and William Godwin's Mr. Faulkland in Caleb Williams (1794); he was also noticeably similar to René, the hero of Chateaubriand's novella of 1802, although Byron may not have read this.[2]

After Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, the Byronic hero made an appearance in many of Byron's other works, including his series of poems on Oriental themes: The Giaour (1813), The Corsair (1814) and Lara (1814); and his closet play Manfred (1817). For example, Byron described Conrad, the pirate hero of his The Corsair (1814), as follows:

That man of loneliness and mystery,

Scarce seen to smile, and seldom heard to sigh— (I, VIII)

and

He knew himself a villain—but he deem'd

The rest no better than the thing he seem'd;

And scorn'd the best as hypocrites who hid

Those deeds the bolder spirit plainly did.

He knew himself detested, but he knew

The hearts that loath'd him, crouch'd and dreaded too.

Lone, wild, and strange, he stood alike exempt

From all affection and from all contempt: (I, XI)[3]

The Oriental works show more "swashbuckling" and decisive versions of the type. Later works show Byron progressively distancing himself from the figure by providing alternative hero types, like Sardanapalus ("Sardanapalus"), Juan (Don Juan) or Torquil ("The Island"), or, when the figure is present, by presenting him as less sympathetic (Alp in "The Siege of Corinth") or criticizing him through the narrator or other characters.[4] Later Byron was to attempt such a turn in his own life when he joined the Greek War of Independence, with fatal results,[5] though recent studies show him acting with greater political acumen and less idealism than previously thought.[6] The actual circumstances of his death from disease in Greece were unglamourous in the extreme, but back in Europe these details were ignored in the many works promoting his myth.[7]

Public reaction and "fandom"[]

Admiration of Byron continued to be fervent in the years following his death. Notable fans included Alfred Lord Tennyson. He was fourteen at the time of Byron's death, and so grieved at the poet's passing he carved the words "Byron is dead" on a rock near his home in Somerby, declaring the "world had darkened for him" (McCarthy, 555). However, the admiration of Byron as a character led some fans to emulate characteristics of the Byronic hero. Foremost was Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who took the Byron cult to remarkable extremes. His marriage to Byron's granddaughter (McCarthy, 562), taking a "Byron pilgrimage" around the Continent and his anti-imperialist stance that saw him become an outcast just like his hero (McCarthy, 564) cemented his commitment to emulating the Byronic character.

Literary usage and influence[]

Byron's influence is manifest in many authors and artists of the Romantic movement and writers of Gothic fiction during the 19th century. Lord Byron was the model for the title character of Glenarvon (1816) by Byron's erstwhile lover Lady Caroline Lamb; and for Lord Ruthven in The Vampyre (1819) by Byron's personal physician, Polidori. Claude Frollo from Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Edmond Dantes from Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo (1844),[8] Heathcliff from Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1847), and Rochester from Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847) are other later 19th-century examples of Byronic heroes (McCarthy, 557).

In later Victorian literature, the Byronic character only seemed to survive as a solitary figure, resigned to suffering (Harvey, 306). However, Dickens' representation of the character is more complex than that. Steerforth in David Copperfield manifests the concept of the "fallen angel" aspect of the Byronic hero; his violent temper and seduction of Emily should turn the reader, and indeed David, against him. But it does not. He still retains a fascination, as David admits in the aftermath of discovering what Steerforth has done to Emily (Harvey, 309). He may have done wrong, but David cannot bring himself to hate him. Steerforth's occasional outbreaks of remorse reveal a tortured character (Harvey, 308), echoing a Byronic remorse. Harvey concludes that Steerforth is a remarkable blend of both villain and hero, and exploration of both sides of the Byronic character.

Scholars have also drawn parallels between the Byronic hero and the solipsist heroes of Russian literature. In particular, Alexander Pushkin's famed character Eugene Onegin echoes many of the attributes seen in Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, particularly, Onegin's solitary brooding and disrespect for traditional privilege. The first stages of Pushkin's poetic novel Eugene Onegin appeared twelve years after Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, and Byron was of obvious influence (Vladimir Nabokov argued in his Commentary to Eugene Onegin that Pushkin had read Byron during his years in exile just prior to composing Eugene Onegin).[9] The same character themes continued to influence Russian literature, particularly after Mikhail Lermontov invigorated the Byronic hero through the character Pechorin in his 1839 novel A Hero of Our Time.[10]

The Byronic hero is also featured in many contemporary novels, and it is clear that Byron's work continues to influence modern literature as the precursor of a commonly encountered type of antihero. Erik, the Phantom from Gaston Leroux's Phantom of the Opera (1909–1910) is another well-known example from the first half of the twentieth century (Markos, 162), while Ian Fleming's James Bond (if not his cinematic incarnations) shows all the earmarks in the second half: "Lonely, melancholy, of fine natural physique, which has become in some way ravaged . . . dark and brooding in expression, of a cold and cynical veneer, above all enigmatic, in possession of a sinister secret."[11]

A truly Byronic vampire, although not in the same sense as the other examples, has to be Lord Byron himself, in his appearance in the Erben der Nacht-book series by the German author Ulrike Schweikert. In her young adult-series, revolving around a group of teenaged vampires that travel Europe to learn the skills of different vampire-clans, Byron himself appears as a vampire of the Vyrad-Clan, the English clan that dominates London. While he has little impact on the main story, he plays a part in one of the main characters' romantic subplots, as he approaches his love-interest and then manipulates the main character in question, the Italian vampire Luciano, into challenging him to a duell. It later turns out that Byron had intended to loose the duel on purpose, so Luciano could impress his love-interest, Clarissa. This doesn't work as one of the bullets fired during the duell hits Clarissa and almost ends up killing her, as it was made from silver, which is lethal to the vampires in the series. Nonetheless, the way Luciano cares for her after her injury resolves their relationship-problems.

Byronic heroine[]

There are also suggestions of the potential of a Byronic heroine in Byron’s works. Charles J. Clancy claims that Aurora Raby in Don Juan possesses many of the characteristics typical of a Byronic hero. Described as “silent, lone” in the poem, her life has indeed been spent in isolation - she has been orphaned from birth. She validates Thorslev’s assertion that Byronic heroes are “invariably solitaries” (Clancy, 29). Yet, like her male counterpart, she evokes an interest from those around her, “There was awe in the homage which she drew” (XV, 47). Again, this is not dissimilar to the description of the fascination that Byron himself encountered wherever he went (McCarthy, 161). Her apparent mournful nature is also reminiscent of the regretful mien of the Byronic hero. She is described as having deeply sad eyes, "Eyes which sadly shone, as Seraphs' shine" (XV, 45). This was a specific characteristic of the Byronic hero (Clancy, 30). This seems to express a despair with humanity, not unlike the despair present in Byron's Cain, as Thorslev notes. She herself admits to despairing at "man's decline" (XV, 45), therefore this brings her into direct comparison with Cain's horror at the destruction of humanity (Clancy, 31).

References[]

- ↑ Christiansen, 201

- ↑ Christiansen, 201-203

- ↑ Christiansen, 203; sections VIII-XI of Canto I contain an extended account of Conrad's character, see Wikisource text

- ↑ Poole, 17

- ↑ Christiansen, 202

- ↑ see Beaton

- ↑ Christiansen, 202, 213

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Christiansen, 218-222

- ↑ Christiansen, 220, note

- ↑ Amis, 26